Character optimization has been a personal interest for me ever since I started playing D&D in its 3rd edition back around 2004.

Over the years, people who like to play characters that are optimal have earned themselves an undesirable label of “powergamer”, “min-maxer” or “rules lawyer”. Not all of this reputation was unearned.

In response, in 2006, one of the more prolific posters, Caelic, created the 10 commandments of practical optimization in the WOTC boards (the official D&D forum of the time). Today, even though the original forum post has been taken down, the points made by Caelic continue to apply to what we call practical optimization (as opposed to theoretical optimization which is meant purely as a thought experiment and not meant for actual gameplay).

This article tries to summarize and recontextualize these points for D&D 5th edition and the Adventurers League.

1. RAW is a myth

This is THE dirty secret of optimizers. D&D cannot be played entirely by the rules-as-written (RAW), and D&D 5th edition is no exception.

If you actually tried to play D&D 5E RAW, you have yourself an unplayable game. This game is designed to be played and interpreted with common sense – otherwise the 5E ruleset would be millions of pages long.

Common sense is not a bad thing. There has to be some basic level of agreement between D&D players, otherwise the game is meaningless.

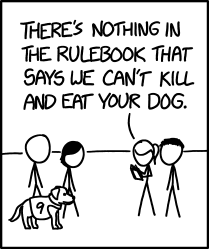

2. “The rules don’t say I can’t” is not practical optimization

This is the flip side of the first point. D&D is designed with a lot of ambiguity between what you explicitly can or cannot do. In D&D 5th edition, there are no rules that say a human can’t have 157 arms, or that a dead person can’t go around attacking enemies with a greatsword.

That’s why you need a DM to close the rules gap. A practical build should rely on what the rules say can be done and avoids going into the realm of what is only not expressly forbidden in the rules.

If you ask for an explanation on how a trick works, and the person explaining to you tells you, “The rules don’t say I can’t”, that’s probably a sign you aren’t dealing with practical optimization.

3. Mistakes happen; Intent matters

Sometimes the rules are written, but written wrongly or with unintentional implications. For example, the pre-Tasha’s Steel Defender used to gain seemingly permanent and nigh-unlimited boosts to its stats if its Artificer player gained temporary boosts to their proficiency bonuses, such as through the Ioun Stone of Mastery. This was clearly not something intended by the rules and indeed it was later corrected in the reprint when Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything came out.

Sometimes, there are mistakes or omissions in the rules as written. In these situations, Jeremy Crawford tweets out rulings and Sage Advice that serve to demonstrate the writers’ intent for their rules. While these may not be RAW, these clarifications should serve as a guide on how to handle a particularly ambiguous situation.

Its one thing to say “This rule is worded vaguely, so I don’t know its intent” and another completely to say “This rule is worded vaguely, so I can ignore the intent of this rule”.

4. If it seems too good to be true, it probably is

Sometimes you run into a “trick” that seems too good to be true; maybe you thought of it yourself or you heard about it from someone else. Go back and scrutinize the relevant rulebooks, and oftentimes you will realize that one of the following is happening:

- The trick relies on an ambiguous reading of the rules (see 1 and 2.)

- It involves making use of a loophole in the rules that was unintended by the designers (see 3.)

- There was a misremembering of what the rules actually say

The third point is especially insidious because oftentimes when a trick is repeated without sufficient consultation of what is actually written in the rules, the shaky foundation that a trick rests on is assumed to be “by RAW”.

If you were the person who came up with the trick, always go back and check. If it works, great! Otherwise, the best course of action would be to accept it and move on. There’ll always be another idea or build next time.

5. Tricking the DM is Bad

This one is fairly obvious but needs pointing out – D&D is a game that is played with your friends, including your DM. Deceiving your friends is a Bad Thing. Don’t do it.

But even setting that aside, trying to trick or deceive (or even bully) your DM to allow your “broken build” basically puts the two of you into an arms race situation. Don’t get into an arms race with your DM – the DM always wins.

Be honest with your DM on what you want to do – and if they say “No”, deal with it. Oftentimes, people will try to sneak a trick into the game or fast talk DMs into “letting it slide” – that’s a surefire way to get the DM annoyed at you.

Some Parting Words

Practical optimization should be the standard for all D&D players who strive to call themselves character optimizers.

Practical optimization should be the standard for all D&D players who strive to call themselves character optimizers.

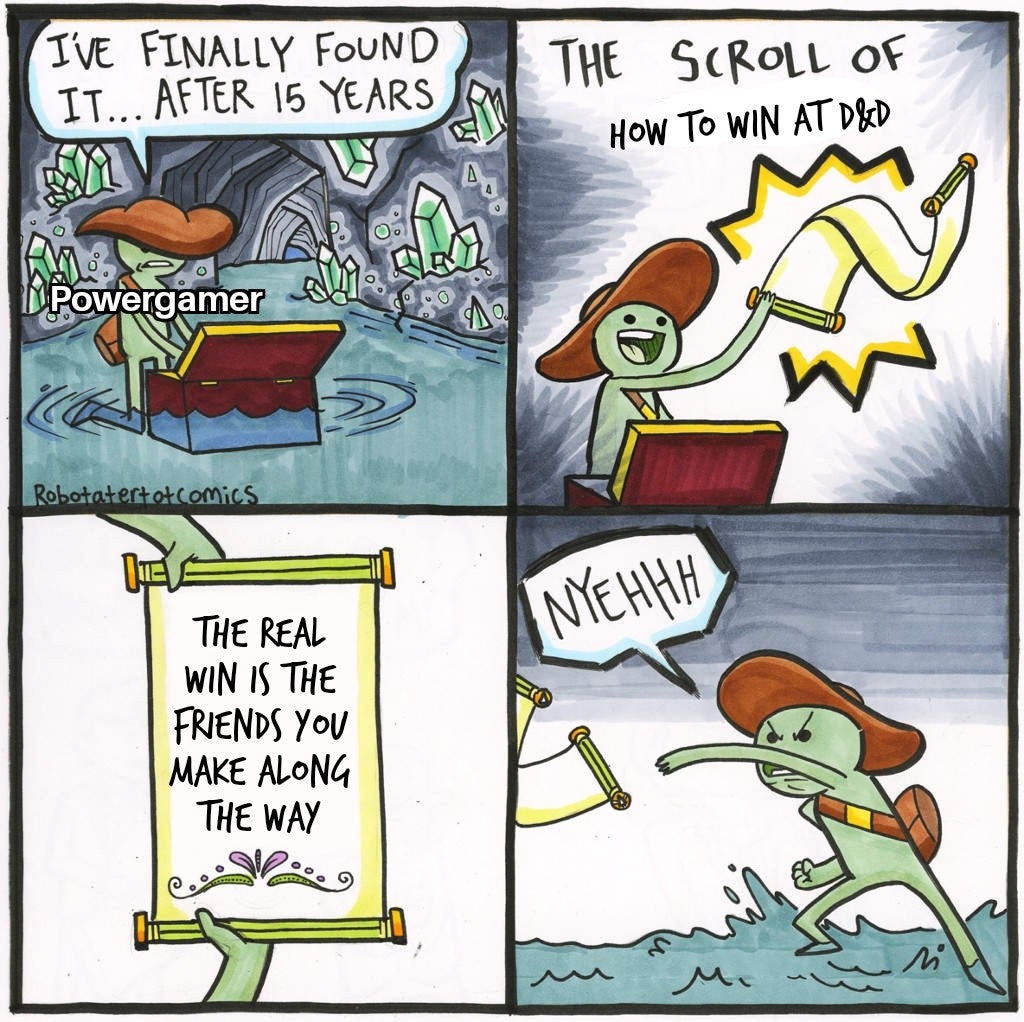

One of the problems with optimizers has always been in fitting in with the rest of the group. There is a tendency to view the DM-player relationship as an antagonistic one, where they have to “beat the DM” instead of working with the DM and the rest of the players in order to have fun at the game together.

The effectiveness of your character is as much a function of your own character building skill and knowledge as it is an ongoing conversation between player and DM. Practical optimization will go a long way to helping both yourself and the people around you enjoy playing D&D together.

Do you have any questions or comments about this article? Do you think I missed mentioning anything? What else about character optimization would you like me to touch on next time? Do let me know, either privately, or on the TLB discord: https://discord.gg/Dx9qaKt

Until next time!

Share this:

- Share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp